The impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly visible and severe. In the UK, this includes record-breaking heatwaves, frequent flooding and drought-driven wildfires. While these immediate effects are alarming, the broader consequences of climate change are more complex and far-reaching, with significant implications for human health, financial systems and the wider economy.

The regulators’ view: from nice-to-know to need-to-comply

UK regulators are increasing pressure on pension funds and (re)insurers to address climate-related risks, requiring them to use scenario analysis where possible. The IFoA has also issued multiple Risk Alerts for actuaries, most recently warning that “the climate may change more quickly than some models predict”.1 Climate change has shifted from “nice-to-know” to a regulatory requirement for decision-making and planning.

Scenario modelling: exploring uncertain futures

Many of the climate-related events and health impacts we now face have never happened before and will not be captured by simply projecting historical trends. This is where narrative-based scenario modelling becomes essential. It is one of the most powerful tools we have to make sense of uncertainty. By exploring the impact of possible future events, we can stress test our assumptions while understanding how these events might play out over time. For longevity in particular, crafting scenarios can help us grapple with big-picture forces like climate change, shifting demographics, and evolving public health trends, all of which unfold over decades with little historical precedent.

(Re)introducing our scenarios

When we published our first Hot and Bothered? paper we highlighted the potential impacts of climate change on longevity. Since then, the industry has made significant progress in developing a shared understanding of plausible climate futures, supported by frameworks like the Representative Concentration Pathways (‘RCPs’)2, Shared Socioeconomic Pathways3 (‘SSPs’), and Network for Greening the Financial Systems (‘NGFS’) Scenarios.4

In response to this evolving thinking, we’ve updated and reframed our own longevity-related scenarios to better align with these widely recognised pathways. This ensures they remain relevant, credible, and compatible with broader climate and financial risk assessment.

These scenarios, when considered alongside other risks, can help pension funds and (re)insurers integrate the issues of climate change and resource constraints into their broader risk management frameworks. Please note that the scenarios are designed to help stress test risk management plans. We have not assigned any probabilities to these scenarios and the middle scenario should not be taken as a view on the ‘most likely’ or central scenario. Nor do we suggest that this is the full range of potential outcomes.

Scenario 1: Sustained stagnation

This is our most pessimistic scenario, where limited adaptation and mitigation lead to severe global impacts. Initially, there is a lack of response to resource and environmental risks until they cause significant societal harm. By the time the world reacts, climate change has caused crop failures and food shortages.

Extreme temperature fluctuations and prolonged heatwaves lead to increased mortality, especially among the elderly, many of whom are pushed beyond their ‘frailty point’, where heat exhaustion accelerates morbidity. Although current cancer vaccines show promise, their impact is hindered by manufacturing constraints and diet changes due to food scarcity. This results in an upward trend in both cancer and cardiovascular disease. Meanwhile, antibiotic resistance rises. Despite initial drug breakthroughs using artificial intelligence, the development of new antibiotics remains limited.

Warmer climates also bring new infectious diseases to the UK, increasing infection rates back to levels not seen in over a century. Pandemics like COVID-19 become common, exacerbated by strained resources that undermine NHS capacity. As a result, the quality of care for age-related conditions, such as frailty and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, deteriorates further.

Scenario 2: Turbulent times

In this scenario, some adaptation occurs but progress is too slow to fully offset the limitations of finite resources and the climate impacts already locked into the system. This scenario can be viewed as largely following the current course, where political will for adaptation and mitigation exists, but progress moves slowly.

This gradual pace of change leads to a range of consequences, including rising fuel prices and intensified competition for resources. In the UK, these pressures translate into financial strain and funding limitations for the NHS. At the same time, reduced access to and higher costs of imported food stocks negatively affect public health. Lower-income groups face challenges affording their basic needs, leading to stagnating life expectancy.

Scenario 3: Rapid response

This more optimistic scenario envisions rapid (but plausible) response to climate change, driven by public awareness, technological innovation, and decisive legislative action.

These efforts lead to meaningful environmental improvements and health benefits. Increased adoption of electric vehicles, public transport, and active travel methods (such as walking and cycling) lead to better health and cleaner air. At the same time, significant improvements in green energy availability and healthier diets also reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The UK invests in better protection against extreme temperatures, enhancing crop security and home insulation. This results in fewer cold and heat-related deaths, as well as more efficient emergency services. Improved diet, exercise, and air quality lead to lower incidences of cancer, cardiovascular disease, dementia, and respiratory diseases. Overall, these factors contribute to a smooth projection of longevity, consistent with a fast and orderly transition to a sustainable future including life expectancy increases.

Impact on period life expectancy under each scenario

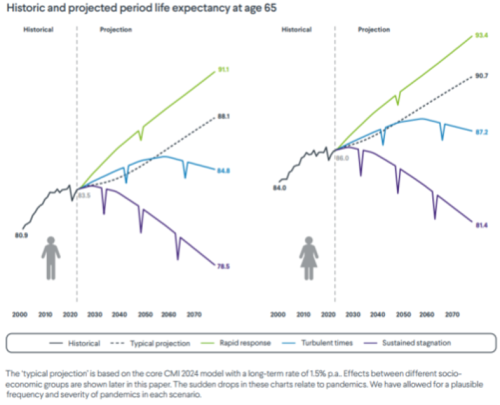

The future pathway for longevity varies markedly under our three climate-related longevity scenarios. The charts show this based on the widely used measure of ‘period’ life expectancy, under each of the three scenarios and for males and females. These are life expectancies based on the observed mortality rates at each age for a given year and apply to the England and Wales population.

Figure 1: Historic and Projected Period Life Expectancy at Age 65

Source: Club Vita LLP, Still Hot and Bothered, 2025. Reproduced with permission from Club Vita LLP

Period life expectancies are objective and widely used in national statistics. However, they are a ‘snapshot’ of mortality at a single point in time. For example, the 2025 period life expectancy assumes that an individual will experience the mortality rates observed in 2025 for the rest of their life, without accounting for future changes such as medical advances or the resolution of a pandemic. As a result, period life expectancies are highly sensitive to short-term shocks like COVID-19 and do not reflect how long someone alive in that year is actually expected to live.

Impact on cohort life expectancy under each scenario

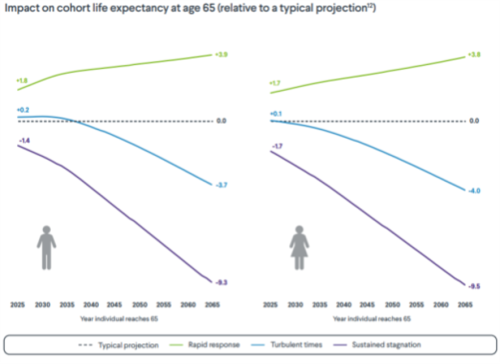

A more relevant measure of life expectancy for pension funding is ‘cohort’ life expectancy – a measure of the expected future lifetime of an individual allowing for the impacts of climate change over their lifetime. The charts below show the impact on cohort life expectancy from age 65 for different generations. This is shown relative to a typical assumption currently used by many pension schemes.

Figure 2: Impact on Cohort Life Expectancy at Age 65 (Relative to a Typical Projection

Source: Club Vita LLP, Still Hot and Bothered, 2025. Reproduced with permission from Club Vita LLP

These charts show the generational impact of plausible climate change scenarios. As expected, the most optimistic outlook (in terms of life expectancy) emerges under the rapid response scenario, where proactive measures lead to steadily improving longevity outcomes. In contrast, the sustained stagnation scenario shows a worsening picture over time, highlighting the long-term consequences of failing to address climate risks.

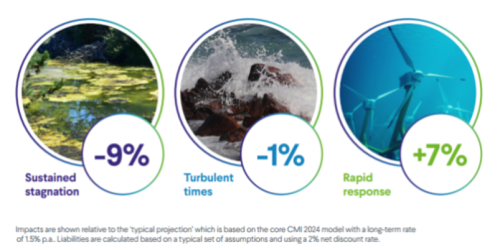

What might the liability impact be for a typical pension scheme?

The figures below provide a broad estimate of the impact on liabilities under each scenario. This is based on the typical age profile of a closed, mature defined benefit pension scheme.

Figure 3: Liability Impact Under Each Scenario

Whilst our sustained stagnation and turbulent times scenarios both reduce the liabilities of the pension scheme looking at longevity in isolation, it is important to appreciate that these scenarios are likely to be accompanied by different outlooks for interest rates and asset values.

Beyond longevity: broader impacts on pension scheme risk

This article is focused on how climate change and resource constraints could affect UK longevity. However, when stress testing risk management plans, it is important for pension funds and (re)insurers to consider the broader impact of these scenarios across all risks. The events described in the longevity scenarios are also likely to affect key financial and operational areas, including asset values, interest rates, inflation and sponsor covenant strength. Even in scenarios where longevity assumptions appear favourable, broader economic distress may still result in significant challenges for pension funds and (re)insurers.

To wrap up

Scenario analysis is an effective way to try to quantify the potential impact of risk associated with climate change. It also provides a more accessible way of visualising the possible future effect of longevity risk and is a useful way to stress test risk management plans. We hope the scenarios presented in this article foster meaningful discussion around climate-related risks and support a more effective integration of longevity risk into broader risk management strategies. Even if these future longevity events do not represent a best estimate of the future, they should not be ignored – in risk management, preparing for what could happen is more important than trying to predict what will happen.

Amy Walker is Actuary and Client Delivery Lead UK at Club Vita

Footnotes:

- https://actuaries.org.uk/media/ue4hdq3l/risk-alert-climate-change-scenario-analysis.pdf

- https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/shared-socioeconomic-pathways

- https://www.ngfs.net/ngfs-scenarios-portal/explore

This article is an abridged version of the original, Still Hot and Bothered?, the full version of which (including the relevant reliances and limitations) can be found here https://www.clubvita.net/uk/news-and-insights/still-hot-and-bothered).

Any views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and may not necessarily represent those of Longevity & Mortality Investor or its publisher, the European Life Settlement Association